A typical ball bearing consists of inner and outer raceways, a number of spherical elements separated by a carrier, and, often, shields and/or seals designed to keep dirt out and grease in. When installed, the inner race is often lightly pressed onto a shaft and the outer race held in a housing. Designs are available for handling pure radial loads, pure axial (thrust) loads, and combined radial and axial loads.

Ball bearings are described as having point contact; that is, each ball contacts the race in a very small patch – a point, in theory. Bearings are designed such that the slight deformation the ball makes as it rolls into and out of the load zone does not exceed the yield point of the material; the unloaded ball springs back to its original shape. Ball bearings do not have infinite lives. Eventually, they fail from fatigue, spalling, or any number of other causes. They are designed on a statistical basis with a useful life where a certain number are expected to fail after a set number of revolutions.

Manufacturers offer single-row radial bearings in four series over a range of standard bore sizes. Angular contact bearings are designed to withstand axial loading in one direction and may be doubled up to handle thrust loading in two directions.

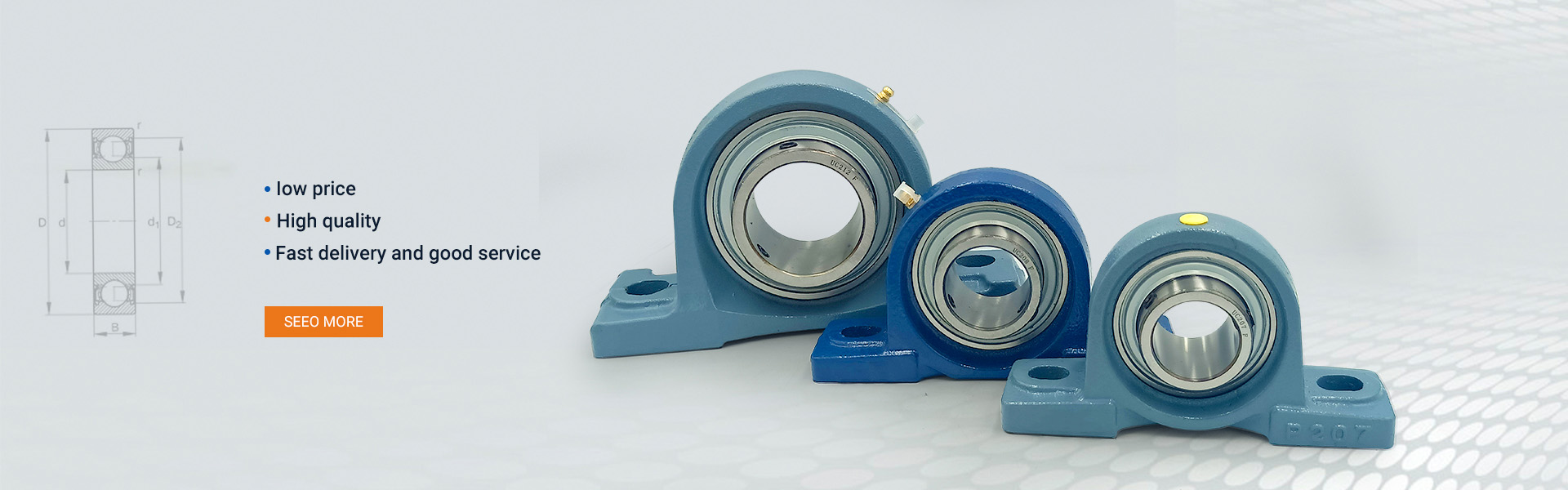

Shaft and bearing alignment play a critical role in bearing life. For higher misalignment capacity, self-aligning bearings are used.

To increase radial-load capacity, the bearing carrier is eliminated and the space between the races is filled with as many balls as will fit—the so-called full-complement bearing. Wear in these bearings is higher than those using carriers because of rubbing between adjoining rolling elements.

In critical applications where shaft runout is a concern—machine tool spindles, for instance—bearings may be preloaded to take up any clearance in the already tightly-toleranced bearing assembly.

Post time: Sep-01-2020